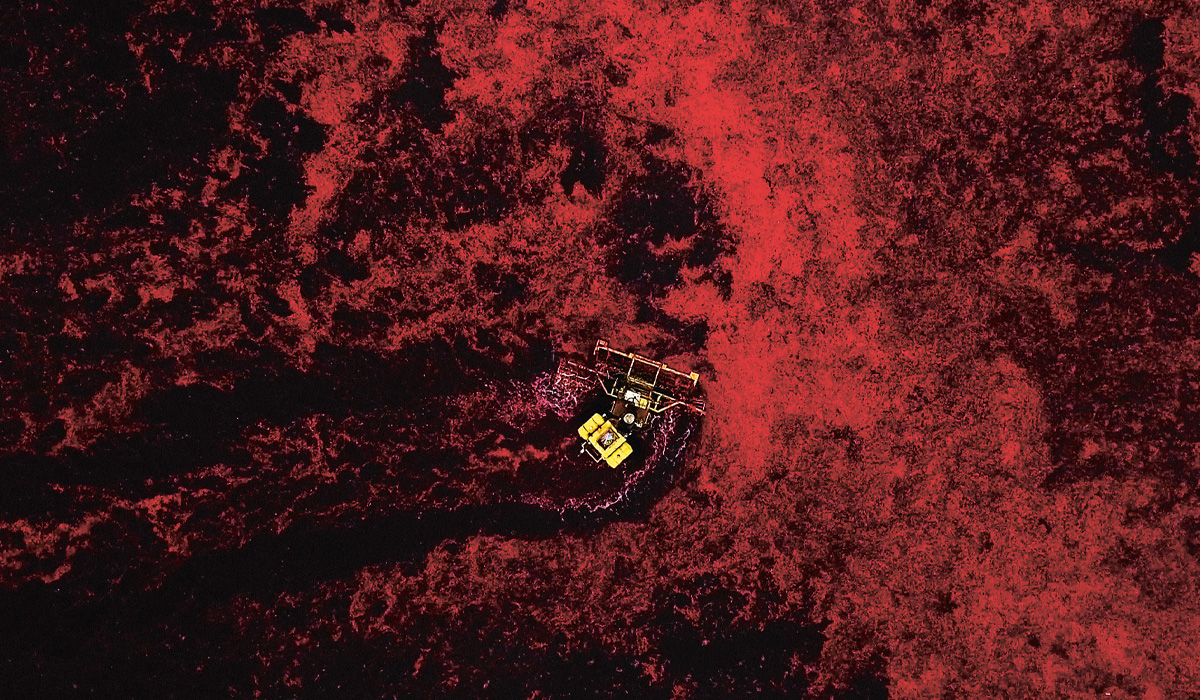

Once the berries are separated from the plants, employees collect the fruit using a long plastic hose they call the “cranbarrier.”

Tom Larrabee (left) and his son Nick are passionate cranberry farmers. Together, they supply Diana Food with this red fruit.

»I’m pretty sure my father had cranberry juice in his veins instead of blood.«

Tom Larrabee Cranberry farmer

“I’m pretty sure my father had cranberry juice in his veins instead of blood,” says Tom Larrabee. The gray-blond man with a wine-red sweatshirt and a gray baseball cap smiles while he says this, but he’s serious. “My family has been cultivating these vines for over 60 years – and there is simply nothing better than bringing in a harvest.” The whole process clearly fills the 59-year-old with pride and joy. “When the plants grow, the fruits ripen and I can finally harvest them – there’s just something very satisfying about that.”

Tom Larrabee is employed by the Nantucket Conservation Foundation and is responsible for the 100 hectares of cranberry fields on Nantucket Island. The island is located on the east coast of the United States, just a few dozen kilometers from Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard. The vines there grow in two large tracts of land. They belong to the Foundation, which owns almost one-third of the land, manages farms like the cranberry farm and invests all its profits back into the protection of nature.

For Tom Larrabee, agriculture is much more than just a job: It’s his passion. It’s also a family assignment. Starting in the 1950s, his father worked as a cranberry farmer on Nantucket Island practically every day until his passing in 2016. Tom Larrabee needed some time and space, though, before he was ready to take on the family business. After high school, he wanted to get off the island and see the world. He joined the army and traveled to all continents as a Marine. After his military service, he finally settled down with a car workshop, house and summerhouse on the South Carolina coast. He met his wife, who is also from the east coast, and became the father of two children.

Maxime Gravel (middle) purchases the cranberries for Diana Food on Nantucket Island.

After harvesting, the cranberries are pumped onto a vibrating conveyor and loaded onto a truck.

On the mainland, the cranberries are washed, presorted and packed into wooden containers.

Everything seemed to be settled. But after the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001, the family decided to move back to Nantucket. “We wanted to be closer to our relatives and my father needed my help. I’ve been here ever since, and I can’t imagine doing anything else.”

Conversion to organic farming

Over the past few years, Larrabee and his team have invested in sustainable agriculture and made the switch from conventional farming to organic farming. His son Nick played a key role in this transition as a foreman for the Foundation. It’s evident he is just as enthusiastic as his father. The 23-year-old combs through the cranberries in one of the fields. The vines meander over the ground, creating a tangled weave. With a quick movement, he gets up. “Look, there are four berries on this upright branch, which is very rare,” he shouts with a glow in his eyes.

The young man studied sustainable agriculture at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst and knows exactly how to produce organic cranberries. He explains in detail why pesticides aren’t necessary and how he uses ecological fertilizers in the spring and summer. His father nods. Organic farming was a logical next step in his endeavors to protect the natural beauty of his childhood home. Each hectare of farm land helps keep four to five nearby hectares in good shape. “We’ve seen many more plant species and animals here since we switched,” says Tom Larrabee. He regularly observes white-tailed deer, snapping and ornamental turtles, tree frogs and water snakes as well as birds such as osprey, Canada geese and mallards. Even the bees, which pollinate the cranberry blossoms, now appear in greater numbers once again. There is also a financial incentive for the farmer in planting organic fruit. He doesn’t harvest as much as when using conventional methods, but the fruit does sell at a higher price. And in time, when the fields are in full operation, he is confident that the yield will also adapt.

As General Manager, Guy Durand is in charge of the Diana Food plant in Champlain.

“To obtain the best products, we need the smaller, dark red and somewhat bitter berries.”

Unique harvesting process

Larrabee uses specially developed equipment for the harvest, which lasts about five weeks. First, he marks the irrigation channels on the dry field with yellow flags. They indicate where he will have to drive the harvester. Then he floods the field with water. With a kind of small combine harvester, he crisscrosses the area in overlapping circles. The machine separates the berries from the vine so that they rise to the surface – air chambers in the fruit make them lighter than water. Two employees wade through the water with a long plastic hose, known as a “cranbarrier”, and gather the cranberries into a ring. From there, they are pumped onto a vibrating conveyor and loaded into a truck. The truck brings the berries to a washing station on the mainland, where they are cleaned, sorted and packed into wooden crates.

Overnight, the berries (around 10,000 pounds per truck) are transported to the Diana Food plant and processed. The plant is located in Champlain, about an hour drive from Quebec City. Here, the vast forests glow in hues of red and yellow in fall. Diana Food processes the fresh fruit, which was harvested one or two days in advance, over the course of about eight weeks. In the remaining months, the company uses frozen fruit or fruit concentrates. “To obtain the best products, we need the smaller, dark red and somewhat bitter berries,” says General Manager Guy Durand. “As a result, we are not competing with the food market because it is the larger and sweeter cranberries that are in demand there.”

The process that Durand quickly highlights seems quite simple: The molecules are extracted from the berries, which are then sold as concentrates or spray-dried powders. However, the steps that the company has developed to achieve this are highly complex and precisely coordinated.

Overnight, the berries (around 10,000 pounds per truck) are transported to the Diana Food plant and processed.

As product manager, Nathalie Richer is responsible for the global health and nutrition portfolio.

For instance, following a quality control check in the laboratory, the fruits have to be heated and juiced in several steps. “We then separate the remaining solids from the liquid components. The liquid is extracted, purified, concentrated and finally standardized,” says Guy Durand. “This is very important for ensuring that we always have the optimal product to sell to our customers.”

Good for your health

For the manufacturers of nutritional supplements, “optimal” means something very specific for cranberries. “The concentration of proanthocyanidins (PACs) in the extract has to remain constant,” says Nathalie Richer. The product manager, who is responsible for the global health and nutrition portfolio, is also in charge of the Urophenol®extract. It is used in the prevention and treatment of urinary tract and bladder infections. 15 % of the purified extract consists of PACs, which are thought to have a particular effect on these ailments (see interview with Sylvie Dodin). “To do this, we have to process the cranberries as efficiently and gently as possible to keep the special functionalities of these molecules intact.”

To learn more about the berries’ capabilities, the company works closely with research institutions such as the Institute of Nutrition and Functional Foods at Laval University in Quebec or the National Research Council of Canada. “Diana Food is currently partnering in four clinical studies that are investigating the health benefits of polyphenols from different locally sourced fruit, such as strawberries or blueberries,” says Nathalie Richer. “Of course, cranberry remains at the heart of our scientific work and we will be completing soon a major clinical study on its mechanism of action on urinary health.“

Click on this link to view a video about the sustainable cultivation of cranberries.

Sylvie Dodin is a gynecologist with 30 years of professional experience and a professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Laval University in Quebec.

“I’m a firm believer in the benefits of cranberries.”

Mrs. Dodin, why are you doing research on urinary tract and bladder infections?

First of all, because these infections are very common worldwide. 50 to 60 % of all women worldwide will experience one of these infections at least once in their lifetime – often with very unpleasant symptoms such as a frequent urge to urinate, pain when urinating and an increased number of red blood cells in the urine. This alone is worth intensive research, but we also need much more research beyond the conventional treatment of these infections.

Why is that?

Many women take antibiotics for a few days as treatment. The problem is that these infections are often recurring, meaning that they occur more than twice in six months or more than three times in a year. If always treated with medication, this can lead to antibiotic-resistant strains. At some point, there would be no more suitable medication. That is why we must find strategies to prevent and treat these infections differently.

How are urinary tract infections triggered?

They are caused by bacteria from the intestinal tract entering the urinary tract. Escherichia coli bacteria are responsible for 90 % of the infections. The bacteria settle in the mucous membranes. There they find sustenance and stay alive.

And what can the cranberry do about it?

The idea actually originated in the laboratory. Cranberries contain a high proportion of proanthocyanidins (PACs). These bioactive substances make it difficult for germs to settle in the mucous membrane. They envelop the bacteria and effectively remove them from the membrane. Several studies have shown that a dose of at least 36 milligrams of PACs per day should help. There are also other effects that we are currently researching. We suspect that the microbial climate in the intestine is also partly responsible for such infections. And we believe that cranberries can have a positive influence here, too.

When talking about the effects of these PACs in cranberries, you seem to take a cautious stance. Why is that?

I am convinced of the effect because I have been able to observe it over all the years I have worked as a gynecologist as well as in research. It has also been proven in dozens of studies. But it must also be said that other studies exist that call this effectiveness into question. Here, it seems that the concentrations of PACs used were often too low, which we believe can lead to ineffectiveness. That is why we have started a new study. We are examining a group of 148 women. Half of them will receive a dose of 37 milligrams of PACs per day, which Diana Food will supply us with, and the control group will only take two milligrams.

How will you measure success?

We will track the number of times the infection reoccurs over a period of six months. At the same time, we are assessing how well the women metabolize the PACs. The molecules can only work if they have been metabolized to a sufficient extent. In the end, I am sure that we will be able to prove the prophylactic and healing effect of cranberries, which have been used this way for a very long time.