Compounds like Spicatanate® are referred to as captives in the technical world and are extremely important to Symrise. “Most of the fragrance ingredients we sell to our customers in our formulations are commodity products. The components are no secret. Anyone could use them and purchase the compounds on the market or even produce them themself,” Sarah Maria Kollenberg explains. Captives, on the other hand, are fragrance ingredients developed and patented by Symrise, which means Symrise is the only company that can use them for a period of 20 years. “Perfumes that we develop entirely in-house are protected if they contain a note based on a captive that is specific to Symrise and cannot simply be recreated with other combinations,” Sarah Maria Kollenberg, Director New Ingredients Management, says. She oversees and optimizes the processes and promotes valuation of the compounds in the Group.

Some of the captives are exceptionally efficient and used in the per mill range to enhance scents, while others may serve as a filler to add volume and account for 10 % to 20 % of the mix. Unlike essential oils sourced from nature, captives are pure substances that are, wherever possible, derived from the by-products of other industries using complex processes based on the principles of green chemistry. Spicatanate®, for example, comes from D-limonene, a waste product of orange juice production. Pearadise®, which smells like pear, was developed from the by-products of corn fermentation. And raw sulfate turpentine oil, which occurs as a natural component of pine during the paper production process, is the base material for a new Symrise compound nearly at the end of its development stage. With its resinous, herbal and green scent, it adds another facet to the Symrise portfolio of sustainable captives.

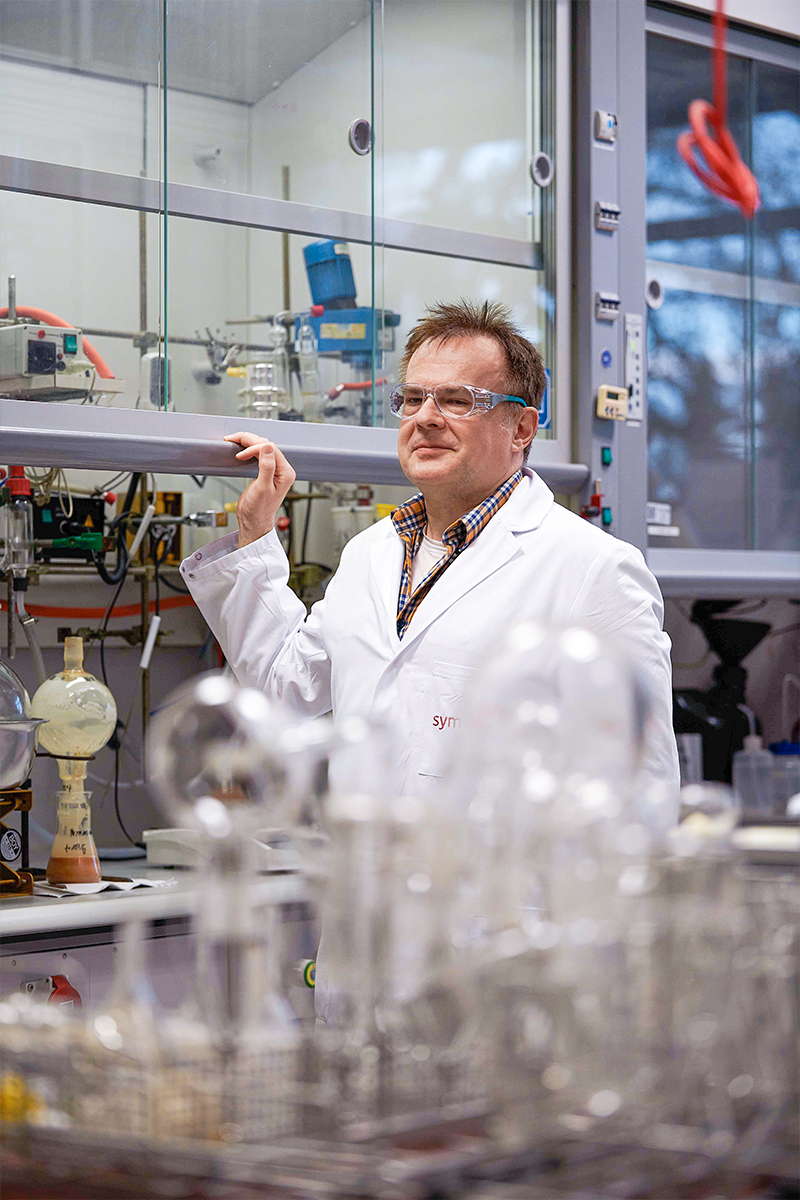

Captives are developed on a variety of foundations that are traditional at Symrise. “Just as it was at the beginning of our company history, it’s often an issue of identifying alternatives to expensive or rare ingredients,” Dr. Nikolaus Bugdahn says, referring to the development of vanillin, which has acquainted many people with the flavor of vanilla for the first time. Research is also inspired by the technologies used by Symrise, Dr. Bugdahn adds. He oversees the synthesis labs in which captives are produced. “In Jacksonville, for example, we use by-products from the paper industry, in which we find components that are attractive to perfumers,” adds head of the lab Dr. Philip Kraft, referencing aspects of the circular economy. In this way, seemingly worthless waste can be transformed into valuable products. Captives can also spark trends in the perfumery sector by replacing nonbiodegradable or nonrenewable fragrance ingredients, offering another form of motivation.