The plants have grown to a sufficient size, and it has been dry as a bone for days, which means the harvest can begin today. First a machine is driven down the field, cutting the plants and forming the clippings into long rows. After that, the mint is left out on the field for two to three days, depending on the outside temperature. “It has to dry out first, otherwise we’d need much more heat for distillation,” explains Terry Cochran, manager of Norwest Ingredients, which he founded with his brother in 1998.

Mint is in their blood thanks to their father, who also cultivated the plant. “Mint is something special. It doesn’t need as much space as corn or wheat, but it does require a lot of knowledge, which also applies to processing,” says Terry. In the coming days, another machine will cut the plant parts on the field into small pieces and load them into “mint tubs,” which at first glance look like conventional truck trailers, but are actually designed specifically to distill the mint right next to the fields. Terry Cochran leads the group to a gravel area nearby, where there are a few tubs. “We supply the distillation system with steam, which heats the plant parts for around one and a half hours,” he says, explaining the process. The steam extracts the essential oil from the plant, while subsequent condensation separates the water and oil. “We use what’s left over to increase sustainability,” says Terry. “The farmers either spread it on the fields as a soil nutrient or in some regions, it is added to cattle feed as a fiber supplement.”

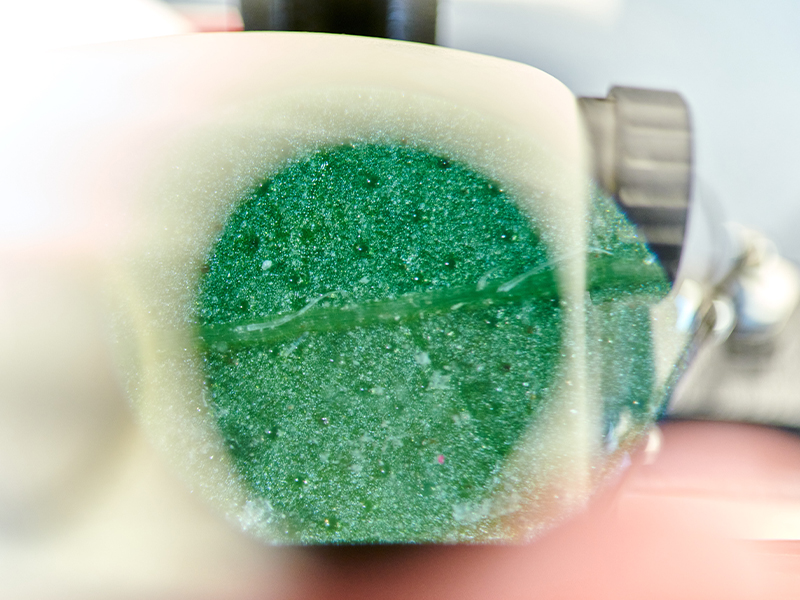

Norwest Ingredients sources around 5 % of its oil from Jet Farms and purchases the rest from approximately 80 farmers in the USA, Canada and India. All of the oils are analyzed in the lab of chemist and Head of Research David Beaver, who’s well acquainted with the variations. He can even smell the slightest changes in the distillates, which he also examines with analysis instruments such as the gas chromatograph. “The oils are often different. Soil, water supply and sunlight have a big impact,” says the 55-year-old, who has been with Norwest Ingredients for 16 years.